The more people work, the less time they have to spend on other activities, such as time with others, leisure activities, eating or sleeping. Furthermore, the more people work, the less time they have to spend on other activities, such as personal care or leisure. Fewer hours in paid work for women do not necessarily result in greater leisure time, astime devoted to leisure is roughly the same for men and women across the 20 OECD countries studied. The chapter also provides an update on working time trends across OECD countries. It shows that usual weekly hours, and the incidence of paid overtime have remained relatively stable over recent decades. Taken together , parallel trends in average annual hours worked, average time spent on leisure, and hourly productivity suggest that productivity increases have not led to extra leisure time.

One possible explanation for this is that workers faced with a decreasing labour share have opted for increases in hourly wages rather than reduction in hours worked. The more people work, the less time they have to spend on other activities, such as personal care or leisure. In Germany, the April 2020 Working Hours Ordinance authorised an extension of daily working time up to 12 hours, while the weekly working time could be extended beyond 60 hours in exceptional cases. In Greece, between March and August 2020, employers who had exhausted the legally prescribed overtime ceilings of their workers, could use overtime without approval from the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs in the respect of maximum daily limits.

In Israel, the Ministry of Labour introduced in March 2020 a temporary permission to work additional hours up to 67 hours a week but no longer than 90 extra hours a month. The permission also included the possibility to work up to 14 hours a day including overtime, up to 8 times a month. In Norway and Sweden,75 national-level collective agreements gave room for more flexibility to actors at the local level regarding the extended use of overtime. As for normal hours, procedural requirements and modalities vary across OECD countries. In Austria and Denmark, averaging of maximum weekly hours requires a collective agreement. In Estonia, Germany, Latvia, Norway and Portugal, the averaging of maximum weekly hours can be introduced pending employees' consent.

In Hungary,25 the Netherlands, Slovenia or Sweden, maximum weekly hours can be averaged unilaterally by employers. The Netherlands' average workweek for full-time employees is 37.3 hours, the second-lowest among the most affluent OECD countries. With only 0.4% of employees working over 50 hours per week, the Dutch have some of the world's best work-life balance. Residents reported that they spend about 15.9 hours per day eating, sleeping, and leisure.

Looking at trends in usual weekly hours and weekly overtime illustrates how the usual week of the average full-time employee in the OECD has evolved in the last decades. However, it cannot be used to assess how the overall quantity of work per full-time employee changed over time, since the latter is also a function of the number of weeks worked , in addition to the usual amount of work per week. However, there are no sources allowing for a reliable comparison of days off taken across countries.

Whaples finds that among the most important city-level determinants of the workweek during this period were the availability of a pool of agricultural workers, the capital-labor ratio, horsepower per worker, and the amount of employment in large establishments. Eastern European immigrants worked significantly longer than others, as did people in industries whose output varied considerably from season to season. High unionization and strike levels reduced hours to a small degree. The average female employee worked about six and a half fewer hours per week in 1919 than did the average male employee. In city-level comparisons, state maximum hours laws appear to have had little affect on average work hours, once the influences of other factors have been taken into account. One possibility is that these laws were passed only after economic forces lowered the length of the workweek.

Overall, in cities where wages were one percent higher, hours were about -0.13 to -0.05 percent lower. Again, this suggests that during the era of declining hours, workers were willing to use higher wages to "buy" shorter hours. As the length of the workweek gradually declined, political agitation for shorter hours seems to have waned for the next two decades.

However, immediately after the Civil War reductions in the length of the workweek reemerged as an important issue for organized labor. Roediger argues that many of the new ideas about shorter hours grew out of the abolitionists' critique of slavery — that long hours, like slavery, stunted aggregate demand in the economy. The leading proponent of this idea, Ira Steward, argued that decreasing the length of the workweek would raise the standard of living of workers by raising their desired consumption levels as their leisure expanded, and by ending unemployment. The hub of the newly launched movement was Boston and Grand Eight Hours Leagues sprang up around the country in 1865 and 1866.

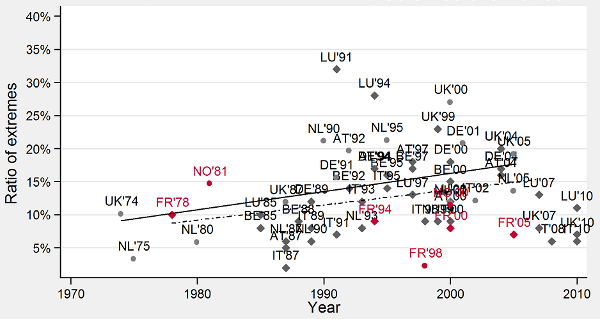

The leaders of the movement called the meeting of the first national organization to unite workers of different trades, the National Labor Union, which met in Baltimore in 1867. The passage of the state laws did foment action by workers — especially in Chicago where parades, a general strike, rioting and martial law ensued. In only a few places did work hours fall after the passage of these laws. Many become disillusioned with the idea of using the government to promote shorter hours and by the late 1860s, efforts to push for a universal eight-hour day had been put on the back burner. Here again, Figure 5.3 does not display a clear-cut relationship between the degree of variation allowed in the rules and the actual degree of variation in outcomes observed. The median amount of paid overtime for full-time employees tend to stay within the limits fixed in the law or in higher level collective agreements in most countries47 that give extensive possibility for the upper limit on overtime to vary.

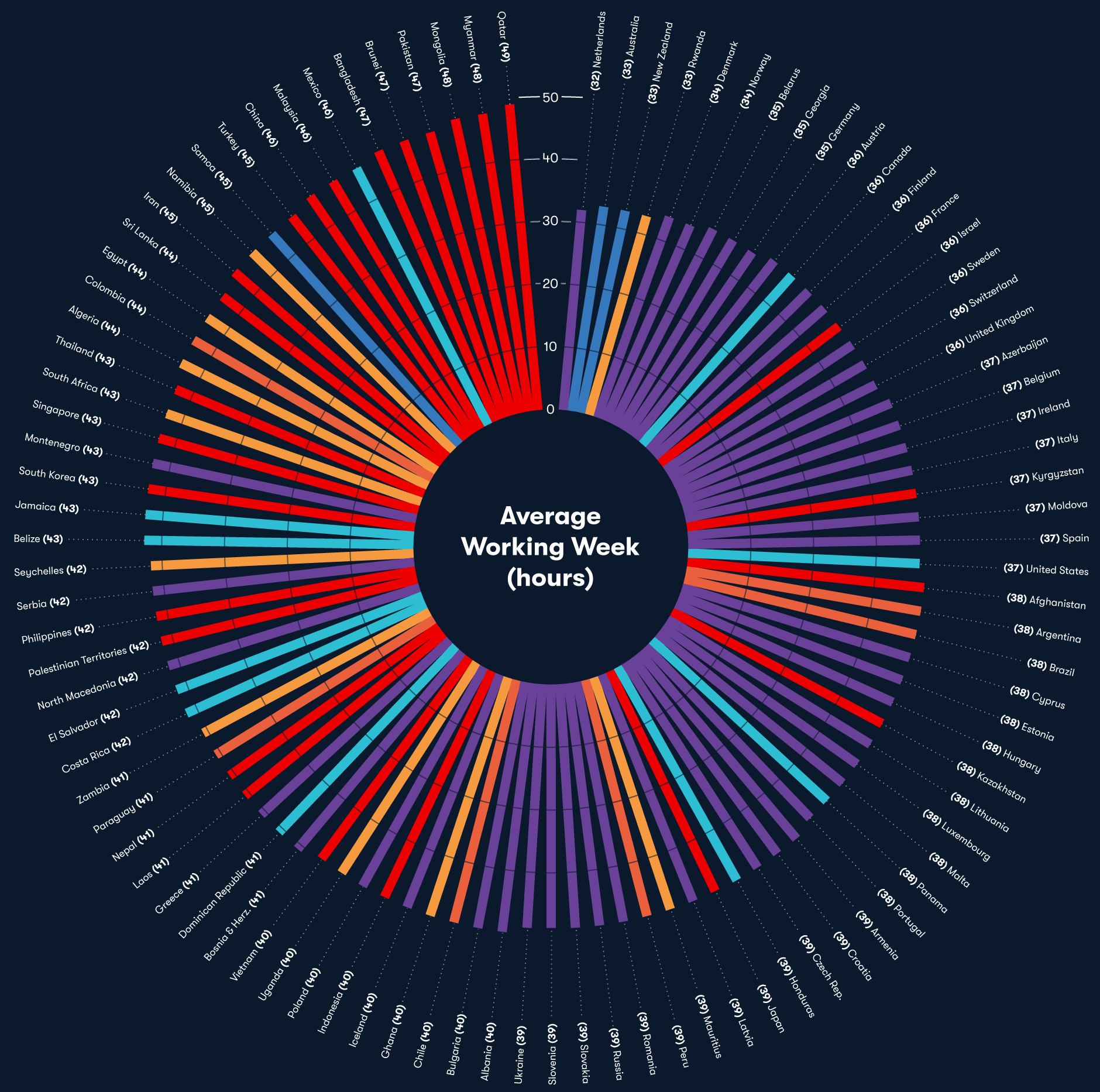

In Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Latvia, and the Slovak Republic, rules governing maximum weekly hours/overtime are likely to be mostly uniform. The upper limit is binding, but there is a limited possibility to use averaging mechanisms, only with the employee's consent or through a collective agreement. In all these countries but Latvia and Denmark, there is a binding minimum compensation for overtime hours . On average in OECD countries, usual weekly hours for full-time employees remained fairly constant between 1995 and 2019, despite small cross-country variations. The median full-time employee usually worked 40.5 hours per week in 2019, ranging from 37 hours in Denmark to 48 hours in Mexico and Colombia. Since the mid-2000s, the incidence of paid overtime has remained stable at just over 7.5% of full-time employees, while that of unpaid overtime decreased slightly, from 6.2% to 5.1%.

For those working overtime, the average number of additional hours is considerable, amounting to 8.3 for paid overtime (7.7 for unpaid overtime), or one additional day per week in 2019. Working time is a crucial variable shaping the labour market and its adaptability to shocks. It can affect key labour market outcomes, such as workers' well-being, productivity, wages and employment. Documenting how OECD countries regulate working time, and understanding how different regulatory settings shape working time outcomes is crucial for policy makers seeking to balance equity, efficiency and welfare considerations. This chapter offers a detailed review of regulations governing working hours, paid leave, and teleworking in OECD countries.

It discusses the role of collective bargaining in negotiating working hours or working time arrangements, and how OECD countries have adapted their working time regulation during the COVID-19 crisis. The chapter also provides an update on working time patterns and trends in time use across OECD countries and socio-demographic groups. It measures how differences across workers in working time outcomes have changed over time and driven inequalities in work-life balance. Actual hours worked include regular work hours of full-time part-time and part-year workers paid and unpaid overtime hours worked in additional jobs and exclude time not worked because of public holidays annual paid leave own. Pilot programs run by governments and businesses in countries such as Iceland, New Zealand, Spain and Japan have experimented with a four-day workweek and reported very promising results.

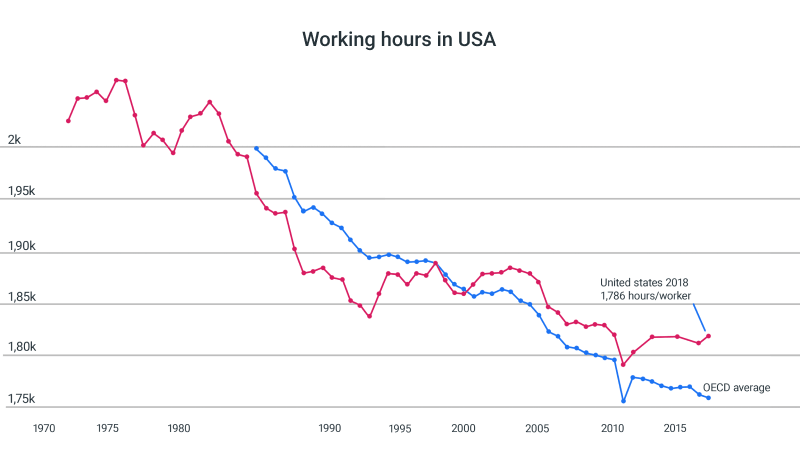

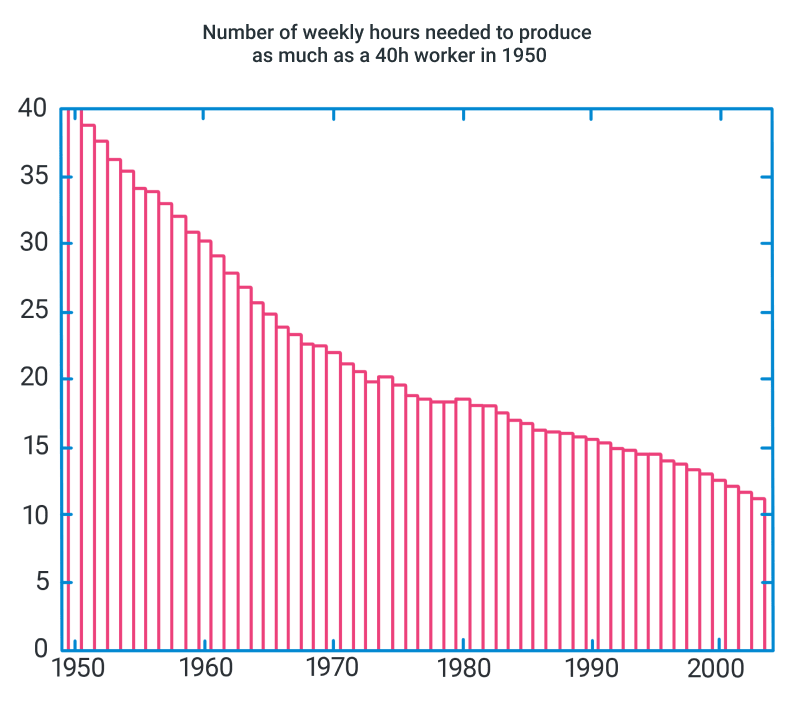

This is a global paradigm shift that will bring into question everything we thought we knew about the workplace. Historically employers and employees often agreed on very long workweeks because the economy was not very productive (by today's standards) and people had to work long hours to earn enough money to feed, clothe and house their families. The long-term decline in the length of the workweek, in this view, has primarily been due to increased economic productivity, which has yielded higher wages for workers. Workers responded to this rise in potential income by "buying" more leisure time, as well as by buying more goods and services. In a recent survey, a sizeable majority of economic historians agreed with this view. Over eighty percent accepted the proposition that "the reduction in the length of the workweek in American manufacturing before the Great Depression was primarily due to economic growth and the increased wages it brought" .

For example, roughly two-thirds of economic historians surveyed rejected the proposition that the efforts of labor unions were the primary cause of the drop in work hours before the Great Depression. The number of RTT days varies every year but is around 10 days annually. Second, LFS data depend on respondent recall and proxy responses, so hours worked and not worked may not be correctly reported due to faulty memory or lack of information.1 Finally, LFS data only cover resident employees.

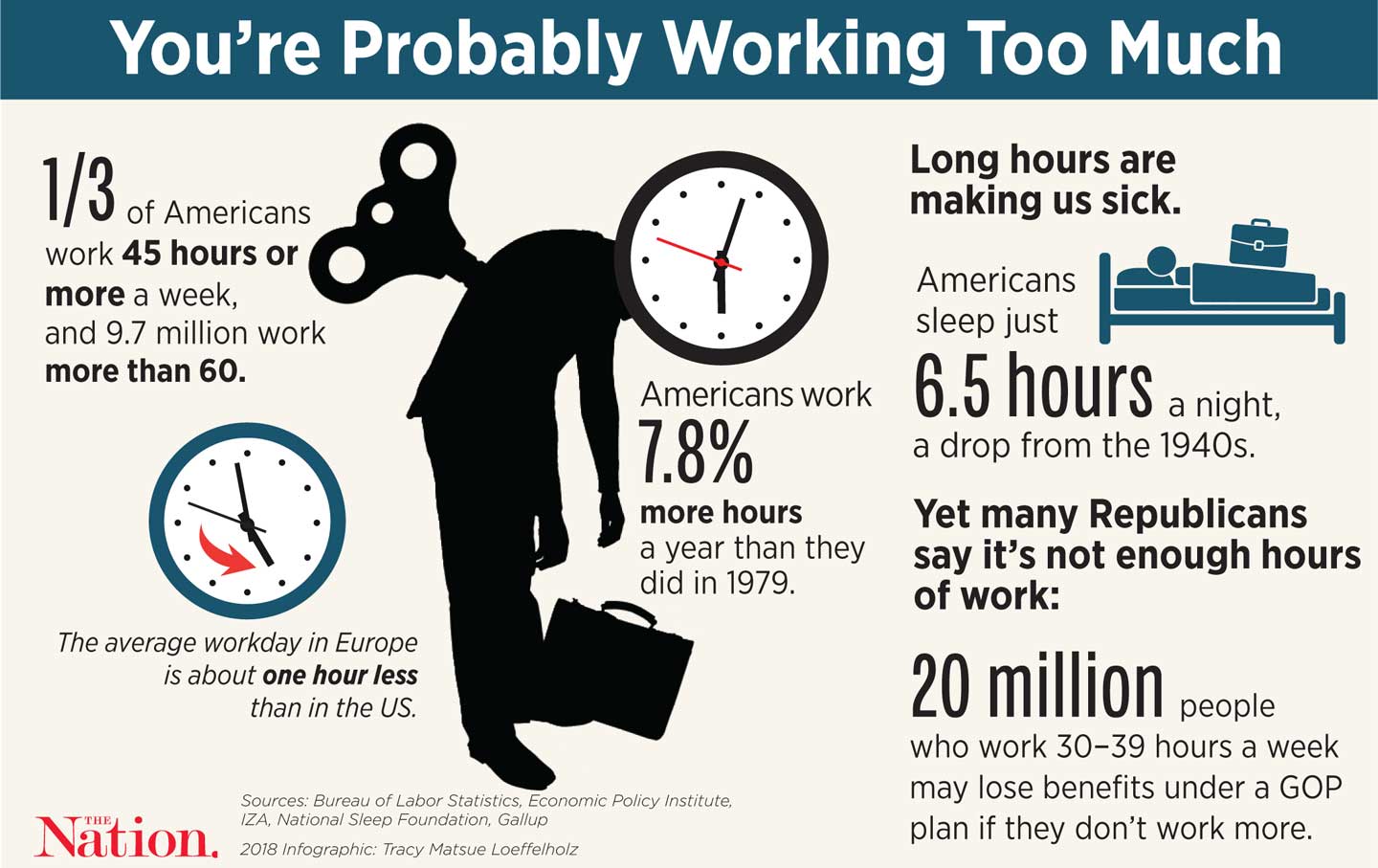

In countries, such as Belgium, Luxembourg or Switzerland, with many cross-border workers, employment data from this source may not correspond to those employed in the country's production of output, thus affecting working hours measures. An important aspect of work-life balance is the amount of time a person spends at work. Evidence suggests that long work hours may impair personal health, jeopardise safety and increase stress.11% of employees in the OECD work 50 hours or more per week.

Turkey is by far the country with the highest proportion of people working very long hours, with 33%, followed by Mexico with nearly 29% and Colombia with almost 27% of employees. Overall, more men work very long hours; the percentage ofmale employees working very long hours across OECD countries is over 15%, compared with about 6% for women. Our economy is composed not only of white-collar workers, and people from all backgrounds should benefit from the changing status quo.

The pandemic left millions of hourly workers unemployed or underemployed. The labor market is becoming more competitive, and workers must feel enabled to demand better working conditions at higher wages, which is why I've introduced federal legislation to lower the overtime threshold from 40 hours to 32 hours per week for non-exempt employees. This legislation does not limit the number of hours a person can work; it entitles employees to begin earning time-and-a-half after 32 hours of work, resulting in a 10% pay increase. Employers would either pay their employees additional overtime or find other workers to fill in the gaps. Because of changing definitions and data sources there does not exist a consistent series of workweek estimates covering the entire twentieth century.

Hours In A Week Work Despite differences among the series, there is a fairly consistent pattern, with weekly hours falling considerably during the first third of the century and much more slowly thereafter. In particular, hours fell strongly during the years surrounding World War I, so that by 1919 the eight-hour day had been won. Hours fell sharply at the beginning of the Great Depression, especially in manufacturing, then rebounded somewhat and peaked during World War II. After World War II, the length of the workweek stabilized around forty hours. Owen's nonstudent-male series shows little trend after World War II, but the other series show a slow, but steady, decline in the length of the average workweek. Greis's two series are based on the average length of the workyear and adjust for paid vacations, holidays and other time-off.

The last column is based on information reported by individuals in the decennial censuses and in the Current Population Survey of 1988. It may be the most accurate and representative series, as it is based entirely on the responses of individuals rather than employers. Since data on usual hours do not include overtime,85 Figure 5.9 displays trends in paid and unpaid overtime for full-time employees in OECD countries for which data are available over the last decade. The average incidence of paid overtime per employee remained relatively stable between 2006 and 2019. By contrast, weekly hours of paid overtime per worker reporting it fell by about one hour between 2006 and 2019. As for the incidence of unpaid overtime, it slightly decreased on average, from 6.2% in 2006 to 5.1% of employees in 2019.

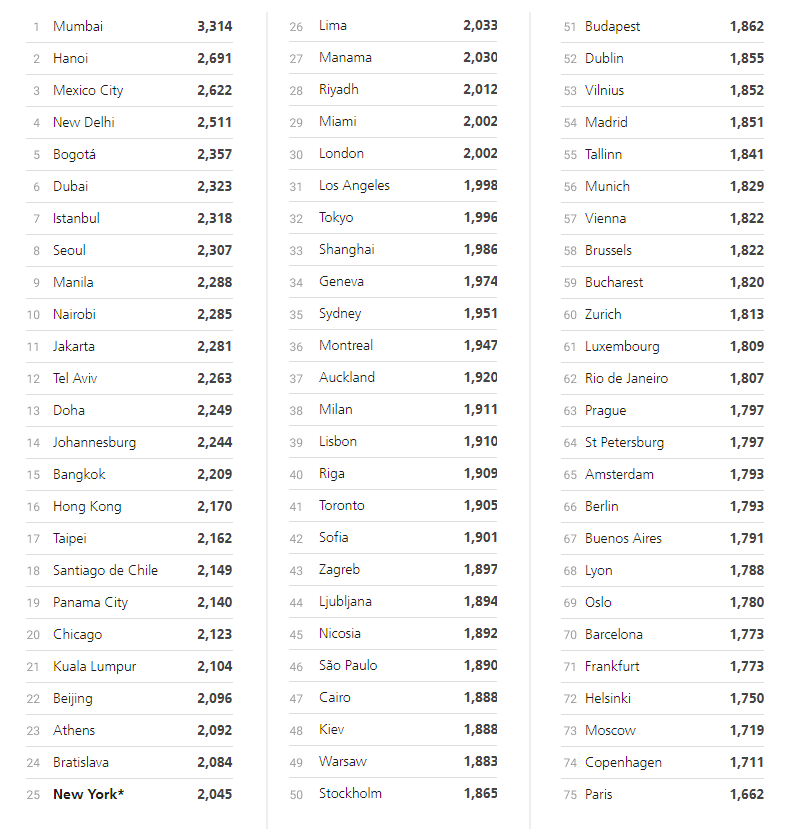

Those working unpaid overtime in 2019 also worked on average close to one hour less each week than in 2006. To determine how long the average workweek is around the world, 24/7 Wall St. analyzed data on the average hours usually worked among dependent employees in 2018 from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Data on the percentage of dependent employees who work part-time -- less than 30 hours a week -- also came from the OECD and is for 2018. Additional data listed is all from the OECD and is for the most recent period available.

All figures are annual except for unemployment figures, which are quarterly. All data on employee hours and part-time work are for dependent employees, meaning it does not include self-employed workers. The swift reduction of the workweek in the period around World War I has been extensively analyzed by Whaples . His findings support the consensus that economic growth was the key to reduced work hours. He finds that the rapid economic expansion of the World War I period, which pushed up real wages by more than 18 percent between 1914 and 1919, explains about half of the drop in the length of the workweek.

The reduction of immigration during the war was important, as it deprived employers of a group of workers who were willing to put in long hours, explaining about one-fifth of the hours decline. The rapid electrification of manufacturing seems also to have played an important role in reducing the workweek. Increased unionization explains about one-seventh of the reduction, and federal and state legislation and policies that mandated reduced workweeks also had a noticeable role. During the 1920s agitation for shorter workdays largely disappeared, now that the workweek had fallen to about 50 hours. However, pressure arose to grant half-holidays on Saturday or Saturday off — especially in industries whose workers were predominantly Jewish. By 1927 at least 262 large establishments had adopted the five-day week, while only 32 had it by 1920.

The most notable action was Henry Ford's decision to adopt the five-day week in 1926. Ford employed more than half of the nation's approximately 400,000 workers with five-day weeks. However, Ford's motives were questioned by many employers who argued that productivity gains from reducing hours ceased beyond about forty-eight hours per week. Even the reformist American Labor Legislation Review greeted the call for a five-day workweek with lukewarm interest. During the first decades of the twentieth century, arguments favoring shorter hours moved away from Steward's line that shorter hours increased pay and reduced unemployment to arguments that shorter hours were good for employers because they made workers more productive. A new cadre of social scientists began to offer evidence that long hours produced health-threatening, productivity-reducing fatigue.

This line of reasoning, advanced in the court brief of Louis Brandeis and Josephine Goldmark, was crucial in the Supreme Court's decision to support state regulation of women's hours in Muller vs. Oregon. In addition, data relating to hours and output among British and American war workers during World War I helped convince some that long hours could be counterproductive. Businessmen, however, frequently attacked the shorter hours movement as merely a ploy to raise wages, since workers were generally willing to work overtime at higher wage rates. These legal frameworks are sometimes set up in dedicated laws, or included in general labour laws or in national or sectoral collective agreements .

Outcomes observed reflect, at least to some extent, the content of rules on weekly working hours. The very high statutory limits on normal weekly hours in Chile, Colombia, Israel, Mexico and Turkey go hand in hand with a high median in usual weekly hours. The first block introduced the general organisation and governance of working time regulation (e.g. the hierarchy between statutory and negotiated norms and the degree of flexibility in deviating from standards set in the law or in collective agreements at higher levels). The second block was dedicated to the regulation of the amount of hours worked . The third block examined the regulation of leave and public holidays. The fourth block looked at the regulation of the organisation of working time (e.g. unsocial hours and flexible working time arrangements).

The fifth block collected information related to the existence of short-time work and more generally job retention schemes and how they have been adjusted as a response to the COVID-19 crisis . Finally, the sixth block focused on recent reforms of working time regulation. Hours actually worked means hours spent directly on work and excludes things like annual leave, sick leave, public holidays, meal breaks, and commuting time. Unpaid family work in this case generally includes market-oriented work, such as for the family business, but not other unpaid work at home such as childcare, cooking, and cleaning. Since the latter type of unpaid work is typically performed by women, this has large implications for understanding gender differences in labor. We discuss these issues as part of our entry on Women's Employment.

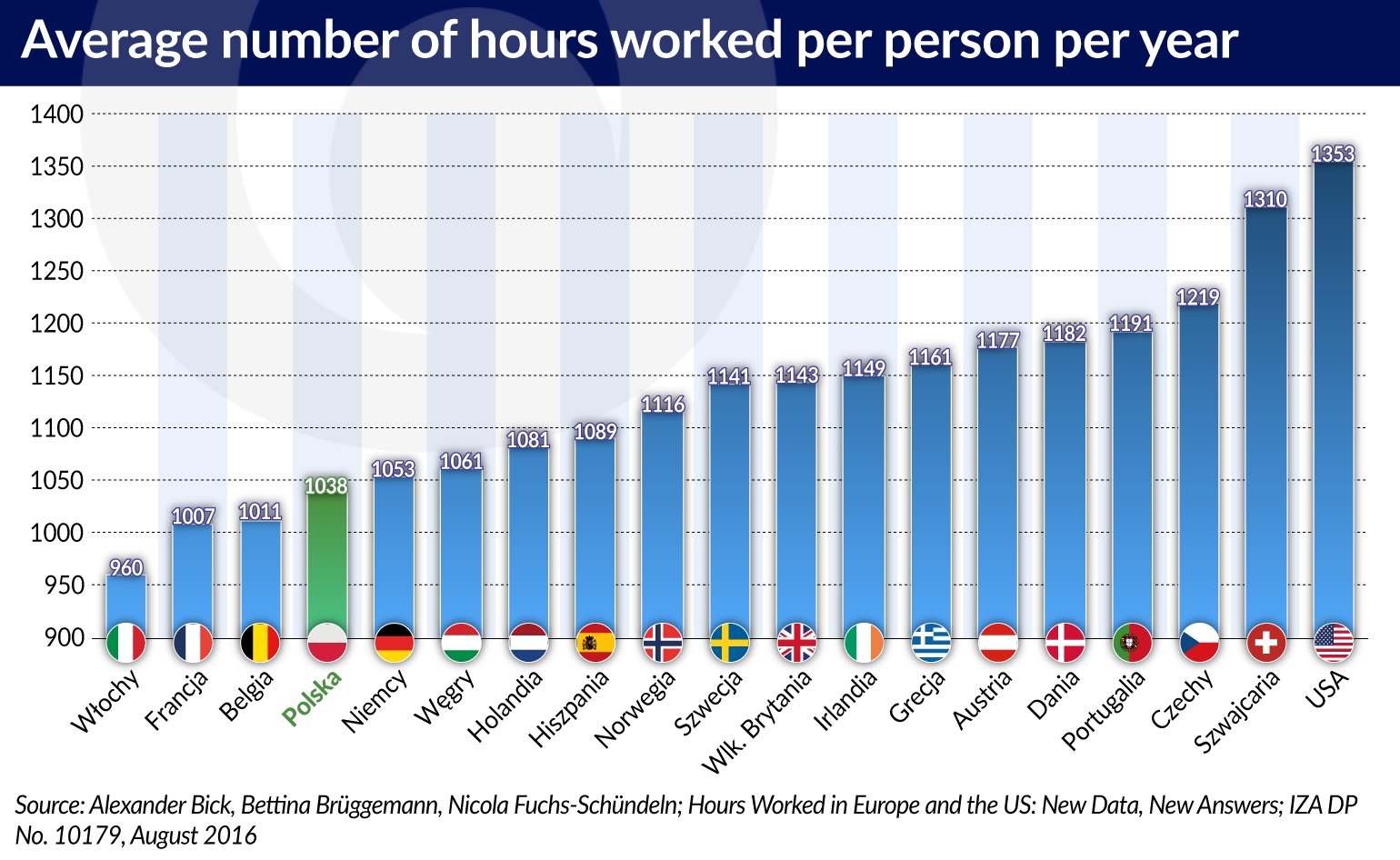

Data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development show that the average annual hours worked by employed people in 2020 were lowest in Germany at 1,332 (25.6 per week). Americans work an average of 1,767 hours , while Canadians work 1,664 hours . Among other places experimenting with four-day workweeks, those in the United Kingdom work 26 hours per week, Spaniards work 30 hours per week, and the Japanese work 31 hours per week. Time poverty and gender roles present significant barriers to women's participation in the labour market. At home, Mexican women spend 4 hours more per day on unpaid care and housework than men. Mexicans also work longer annual hours than workers in all other OECD countries, and have one of the longest average daily commute times in the OECD, after Japan and Korea.

These time constraints complicate work-life balance and present significant challenges for mothers, especially as an increasing share of them are sole parents. The movement for shorter hours as a depression-fighting work-sharing measure built such a seemingly irresistible momentum that by 1933 observers predicting that the "30-hour week was within a month of becoming federal law" . During the period after the 1932 election but before Franklin Roosevelt's inauguration, Congressional hearings on thirty hours began, and less than one month into FDR's first term, the Senate passed, 53 to 30, a thirty-hour bill authored by Hugo Black. Labor leaders were persuaded by NIRA Section 7a's provisions — which guaranteed union organization and collective bargaining — to support the NIRA rather than the Black-Connery Thirty-Hour Bill. Business, with the threat of thirty hours hanging over its head, fell raggedly into line. (Most historians cite other factors as the key to the NIRA's passage. See Barbara Alexander's article on the NIRA in this encyclopedia.) When specific industry codes were drawn up by the NIRA-created National Recovery Administration , shorter hours were deemphasized.

Despite a plan by NRA Administrator Hugh Johnson to make blanket provisions for a thirty-five hour workweek in all industry codes, by late August 1933, the momentum toward the thirty-hour week had dissipated. About half of employees covered by NRA codes had their hours set at forty per week and nearly 40 percent had workweeks longer than forty hours. When Samuel Slater built the first textile mills in the U.S., "workers labored from sun up to sun down in summer and during the darkness of both morning and evening in the winter. Only attracted attention when they exceeded the common working day of twelve hours," according to Ware . This agitation was led by Sarah Bagley and the New England Female Labor Reform Association, which, beginning in 1845, petitioned the state legislature to intervene in the determination of hours.

The petitions were followed by America's first-ever examination of labor conditions by a governmental investigating committee. The Massachusetts legislature proved to be very unsympathetic to the workers' demands, but similar complaints led to the passage of laws in New Hampshire and Pennsylvania , declaring ten hours to be the legal length of the working day. However, these laws also specified that a contract freely entered into by employee and employer could set any length for the workweek. Legislation passed by the federal government had a more direct, though limited effect. On March 31, 1840, President Martin Van Buren issued an executive order mandating a ten-hour day for all federal employees engaged in manual work. Throughout the last 20 years, in the ten OECD countries for which data are available, men consistently spent a larger portion of their day on work-related activities (e.g. paid work, studying, looking for a job) than women.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.